on god, Einstein, religion and world peace: get it all here

My favourite Christmas present was the one I bought myself, a reasonable brick of a tome, recently released, called The Portable Atheist, edited by Hitchens, a reader presented chronologically.

Lucretius' De Rerum Natura starts it off. I first read this work, or a part of it, many years ago in my vie boheme. I was at a friend's party and ended up staying the night, in a sleeping bag. I was a little drunk, but energised, and I raided his bookshelves and settled on Lucretius. Of course I'd never read anything like it, an epic poem in rhyming stanzas [in translation], treating of the essential nature of the universe, arguing that all matter consisted of atoms, and spurning all superstition and religious dogma. I was blown away, and stayed up reading it till dawn. Mais ou sont les neiges d'antan?

I'm already about a third of the way through, and there are contributions from many brave souls, some from the height of religious persecution in Europe, like Spinoza and Thomas Hobbes, whose 'free-thinking' endangered his life on a few occasions. Hume's essay on miracles is here, though it's not so impressive now as when I first read it, and some nineteenth century heavies like Shelley [expelled from Oxford for this particular essay - at least the consequences of speaking were becoming gradually less grim], J S Mill, and Leslie Stephen being very serious and comprehensive. Karl Marx waxes more or less incomprehensible [from his Hegel-shadowed years]. H L Mencken produces an impressive list of dead gods who once held Ozymandias-like sway.

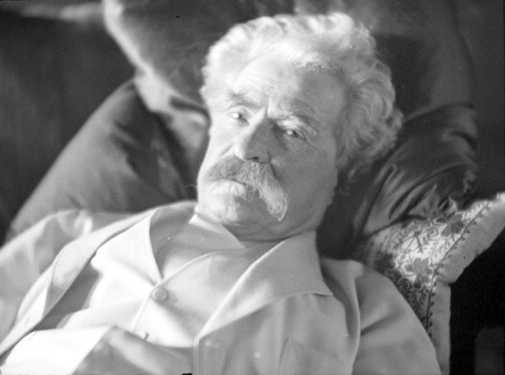

Perhaps the most impressive contribution, and hopefully not just because it's the last one read, comes from Einstein. Not an essay, but a collection of his pronouncements and quotes from letters on the issue from his last years, presumably gathered by editor Hitchens. They're often repetitive but essentially consistent. They're a reminder that Einstein, in his last years, was revered as a kind of seer, much like Mandela today. I think he had a similar personality, a generally benign disposition but with an underlying fierce concern about the state of humanity, about truth and fairness, and a willingness to speak out on occasions, making him the target of many a well-meaning focus group. Much argument has been raised about the nature of Einstein's 'religiosity' but I think his own pronouncements settle the issue [leaving aside the possibility of selectivity and suppression from the editor]. Einstein had no use for a personal god, one who intervened in human affairs and answered prayer. He felt that such a construction was naive and self-serving. He described himself as a 'religious unbeliever', awed by the natural world and its laws, of which he felt we had a far from perfect understanding. He several times cited the pantheistic 'god' of Spinoza, a god identical with nature, with no transcendental - and certainly no anthropomorphic - features.

I'm of course not doing justice to too many of these thinkers with these perfunctory remarks but I've really enjoyed spending time with them over the last few days. Some lost their face slowly and with great reluctance, others were strictly educated into atheism, and others - and I put myself into this group - 'have been so made that they cannot believe' [Pascal's words]. All of them I see as fore-runners, pioneers, like the early feminists, chipping away at the power of religion over people's minds, helping to loosen its grip over educated people, finger by finger. May it never be allowed to rise again, especially not to cast its pall over everyday life.

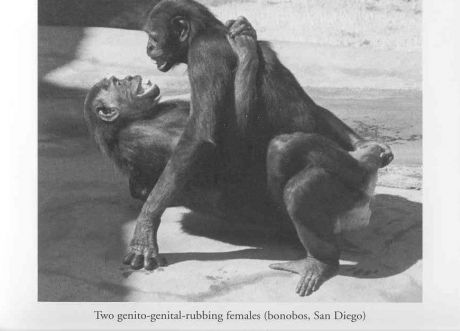

I note that the Pope, [the Goddess bless him] has recently presented a Christmas day message, arguing inter alia that abortion and same-sex marriage [in other words any legitimisation of homosexuality] are as much a threat to world peace as the usual suspects, and that the nuclear family is our greatest bulwark against violence and instability. Obviously he hasn't heard of the bonobo. It's my contention that intolerance and bigotry are a much greater threat to world peace, and the Holy Roman Catholic and Apostolic Church, with its shocking history as well as its current pronouncements, is the greatest promoter of those tendencies in the west. I chafe at the continued existence of such a grotesque institution, and its my fervent hope that it won't survive this century. Interestingly, Einstein also had something to say about their shenanigans:

I am convinced that some political and social activities of the Catholic organisations are detrimental and even dangerous for the community as a whole, here and everywhere. I mention here only the fight against birth control at a time when overpopulation in various countries has become a serious threat to the health of people and a grave obstacle to any attempt to organise peace on this planet.

A retrospective hit, indeed.

Labels: philosophy, politics, the faith hope