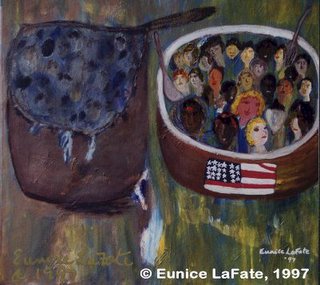

Christianity has evolved and adapted itself from a messianic cult to a world religion, with the key to its spread being the application of universal meaning to the particular circumstances of Jesus’ life and death.

The original Jesus appears to have been both a religious and political figure, apparently standard for messianic figures of the time. The Jewish

Messiah or Mashiach is a king of the line of David (whose very existence is disputed), who will be greater than Solomon and who will bring freedom to the Jews in the land of Israel. He is a figure of fantasy, but more or less completely of this world. Orthodox, conservative, reform and reconstructionist Jews disagree on the meaning of the Mashiach and the world he will help to create for Jews and Gentiles. It helps to keep them occupied.

Christianity also uses the messiah term, choosing Jesus of Nazareth, a radical preacher who found himself at odds with Jewish religious authorities and who was crucified about 1970 years ago, as their messiah, or christ (both terms refer to someone who is ‘anointed’, though what this means isn’t entirely clear).

All of the facts about Jesus are in dispute, and some scholars question whether he ever existed. However, apart from the gospels, none of which appear to have been written in Jesus’ lifetime, there are other non-Jewish references to him – for example, in

Tacitus.

The gospel authors are the first to associate Jesus with the term messiah. They also promoted the idea of his resurrection and the performance of miracles. Belief in miracles was common at the time and strongly promoted by the Pharisees, an emergent group in the complexity of Jewish religious and political life.

The idea of resurrection was no doubt more important than the performance of miracles in the transformation of Jesus into a god, and the creation of a new religion.

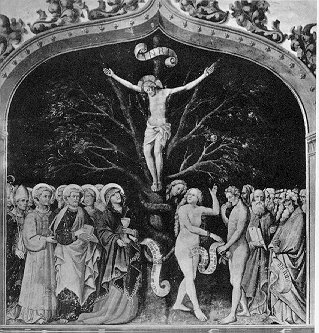

Once resurrection, and thus god-like status, was established in the minds of those willing to believe, the question naturally arose about why Jesus should suffer, be allowed to suffer, allow himself to suffer, such an excruciating death. Ideas then would’ve begun to emerge about the meaning of the death of Jesus (now established as Christ).

It’s hardly surprising that these ideas would’ve been influenced by aspects of the Jewish religion from which Christianity was beginning to emerge, most notably the ‘fall of man’ or ‘original sin’ concept.

The fall of man story is an attempt to explain human imperfection. We were once godlike. Perhaps we were once the children of god, like Jesus. The crime or sin we then committed is unclear. We ate of forbidden fruit. Was it the fruit we ate that caused our decline (amusingly, the pardoner in Chaucer’s ‘The Pardoner’s Tale’ excoriates humankind for the first sin of gluttony, citing this story, and maybe he’s right) or the fact that it was forbidden? If the latter, then the story is telling us that our great crime is disobedience.

But there are other elements to confuse this story. We’re told more than that the fruit is forbidden, we’re told that it contains the knowledge of good and evil. It’s unclear what this actually means, never mind the idea that having such knowledge should be so disastrous for humanity.

But leaving aside this vexed question, the story of the fall tells us that we were thrown out of the garden, that we lost our godly estate, due to sin. Jesus, established as a god, could not challenge the long-established god of the Jews. His followers, promoters and propagandists had to establish a relationship between himself and the god they knew. They had also to maintain monotheism, a great innovation I think, in the god invention business, comparable to the invention of the wheel in the transport business. The idea of Jesus as the son of god was not long in coming. It’s mentioned in the gospels. With this development, the earthly Jesus became the locus of a number of ideas rich with contradiction. He was a god and master, but the son and subordinate of god the father, he was an ordinary man but also man before the fall, without sin, and he was the messiah, king of the Jews, harbinger of the great Jewish time to come, for with the resurrection came the promise of return.

In order to preserve monotheism and its great advantage of control (obedience to the one god), the godness of Jesus had to be incorporated into that monotheism without violating it. The concept of the holy trinity, father and son and holy spirit, or one god in three persons (accept one and you get two more free), has been the subject of mountains of theological speculation and justification, but essentially it’s a convenient fiction to account for Jesus’ divinity, and to release the possibility of Christianity. The triune nature of the god is an especially ingenious development for masking its own purpose in that regard.

So to the complex over-supply of meanings attached to Christ’s being, we must add the meaning attached to his death, and his role of redeemer of sins or, saviour.

The idea that Jesus ‘saves’ or that he ‘redeems’ us or that we achieve redemption through him seems a particularly puzzling one. What do we need saving from?

Of course, the standard response is that Jesus redeems us from our sins. We’re also told that Jesus died for our sins, and that ‘god so loved the world that he gave his only son’. For what? Again the stock answer is – so that whosoever believes in him shall have eternal life.’

Christianity stakes all its credentials, in essence, on an interpretation of Jesus’ death based on suffering and sacrifice, in exchange for the wiping out of ‘sin’; and all sin, be it clearly understood, is born of the first sin, the sin of disobedience. It’s a bizarre scenario, to say the least, and one which, if accepted, puts humans in a more abject position with regard to their own invention than just about any other scenario that has been invented. But of course we humans are far from done with creating bizarre settings for the playing out of our lives.

Labels: the faith hope