Mark Twain v God

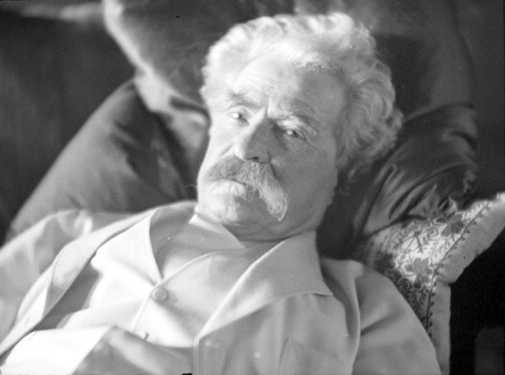

I find myself coming back all too often to religion and my annoyance with it. Having just watched Ken Burns' documentary on Mark Twain, a writer whose earthiness and wry humour I've long admired, I was put in mind again of Twain's anti-religious writings, which I've always been meaning to peruse.

This article provides a useful, if rather disquieting, introduction to Twain's battle with the Judaeo-Christian bigwig. It appears that Twain learned a lesson from the fate of Thomas Paine, whose last major work, the anti-Christian The Age of Reason essentially destroyed his career - in much the same way as the philosopher Descartes learned his lesson from the fate of Galileo. Twain chose not to publish his own anti-Christian writings, which occupied so much of the last phase of his life. They include Letters from the Earth and The Mysterious Stranger [unfinished, and the link is to one of three distinct versions].

To judge from some of the rhetoric of Letters from the Earth, which dwells often on the diseases and disasters the bigwig has inflicted on humanity down the ages, Twain's quarrel with the creator seems to have been largely a result of the illnesses and failures of his declining years. His wife slipped gradually into invalidism and died six years before Twain's own death [in 1910]. His beloved daughter Susie died of meningitis in 1896, and another daughter, Jean, died a year before he did. He'd sunk [without trace] a lot of money into various ill-considered schemes, and was consequently forced into a punishing world-wide lecture tour, including Australia, to recoup his losses.

Such experiences helped produce the embittered tone of his later works, yet I also like to believe his genuine outrage is as much a product of close reading and reflection on the bigwig's shenanigans as presented in the holy book. For example, having rehearsed in my head from time to time my own diatribe on the Perfect One's unconscionable behaviour re the Flood, and the mounting despair and slow, spluttering extinguishment of countless little children at his loving command, I was intrigued to read the following passage - after Twain's comments on the bigwig's murderous antics re the Midianites:

They had offended the Deity in some way. We know what the offense was, without looking; that is to say, we know it was a trifle; some small thing that no one but a god would attach any importance to. It is more than likely that a Midianite had been duplicating the conduct of one Onan, who was commanded to "go into his brother's wife" -- which he did; but instead of finishing, "he spilled it on the ground." The Lord slew Onan for that, for the lord could never abide indelicacy. The Lord slew Onan, and to this day the Christian world cannot understand why he stopped with Onan, instead of slaying all the inhabitants for three hundred miles around -- they being innocent of offense, and therefore the very ones he would usually slay. For that had always been his idea of fair dealing. If he had had a motto, it would have read, "Let no innocent person escape." You remember what he did in the time of the flood. There were multitudes and multitudes of tiny little children, and he knew they had never done him any harm; but their relations had, and that was enough for him: he saw the waters rise toward their screaming lips, he saw the wild terror in their eyes, he saw that agony of appeal in the mothers' faces which would have touched any heart but his, but he was after the guiltless particularly, than he drowned those poor little chaps.Nowadays we're almost bored with the argument [though I use it all the time] that the jealous vindictive god of the OT is the last figure we should set up as a moral exemplar or an object of veneration, and Twain's observations along these lines wouldn't have been original even then, but they're more courageous in the context of his time than they might seem now. They also fit with his outrage and outspokenness at cruelty and brutality in the real world. His lecture tour through Australia New Zealand and South Africa, as well as his Southern upbringing, alerted him to the plight of indigenous peoples under colonisation, and he later wrote fiercely against US imperialism in the Philippines and elsewhere, earning the lasting enmity of Theodore Roosevelt.

Still, much of his railing against God was personal. In Letters from the Earth he dwells much on God's fondness for diseases, as well as the disease-carrying housefly [God's personal favourite]. Typhoid fever was a major killer in his time. His daughter Susie died of spinal meningitis, his wife succombed to illness, and his daughter Jean drowned in the bath during an epileptic seizure. He had a habit of blaming himself for these catastrophes, but what a relief it must have been to rail against the almighty for his toying with humans thus - for being crueller and more callous than we could ever accuse ourselves of being.

Labels: just stuff, the faith hope

3 Comments:

Hmm, It would have been far braver to have published them, but my impression of Twain (and my memory is sketchy) is that his public image was always of far too much importance to him.

I've never liked arguments made in that vein. Leaving Twain aside, they often come from those who do not believe in God. How can you make an argument based on the actions of someone/thing that doesn't exist. Even within the natural context of a conversation where this might arise, it seems to be a tacit disavowal of the atheist's position.

Sorry, i've been meaning to get back to this..

You're right about Twain - reputation was very important to him, but he still spoke out about public issues, making himself many powerful enemies. I suppose, though he would've also had many people congratulating him for his stand, whereas on the god issue he would've felt more isolated.

According to the logic of your argument, we're debarred from discussing the character of Santa, or Huckleberry Finn, or Hamlet, because in doing so we're tacitly admitting these people exist. But of course these people do exist, and their doings and characters are described in texts, or in an oral tradition. It's actually quite legitimate for us to criticise Hamlet for being a ditherer, or Santa for being too fat. The Judeao-Christian god is the same. To me, it's incumbent on the non-believer to point out that the supernatural being that Christians identify with is not just an abstraction of perfect goodness but an anthropomorphised creature with a history, albeit constructed, and a litany of deeds performed, which can be analysed in moral terms, regardless of whether they 'really ' happened or not. After all, we read literature and go to movies which make us laugh and cry and rail over completely non-existent people all the time.

Of course, the many blows that Twain suffered in his last years makes him rail at god in such a way that sometimes you get the impression that he really does believe in him, but can't stand him, which is an interesting position.

Definitely a valid point about Santa & Hamlet et.al and an error on my part.

I shall regroup ;) by saying that perhaps a difference lies in the fact that when we're discussing a fictionl character, whether literary or social, there is a common understanding between the two parties that the character is not real. When discussing "God" in this way with believers, such is not the case.

We have a habit of stripping out qualifications from our speech, like "In my opinion" or "If this were so then..." because they are clumsy and, generally, a given. In this case however, I think those sorts of qualifications are always needed. Especially in a written context, not only to avoid a misinterpretation of what is being stated, but also to avoid misrepresentation.

As with many other lines of argument, I see this one too often used as a means of ridicule rather than and exchange of opinion.

Post a Comment

Subscribe to Post Comments [Atom]

<< Home