the anthropic principle

I've slept in a little, presumably permissible on Boxing Day, and I've done my daily weighing and been appalled by another increase – though presumably permissible after Christmas day. I'll write here for a while and go for a brisk walk or something.

I'm ashamed to say I'd never heard of the anthropic principle before reading Dawkins a couple of days ago – or at least it had never registered with me. What follows will be taken from Dawkins' book and this Wikipedia article.

The anthropic principle has been invoked to explain the just right conditions, not only on Earth but in our universe, that have allowed the development of those very life forms that ask questions about those conditions. It appears to be a statistical principle (though there are various versions of it). That's to say, though it's rare to find a planet that's in a position to sustain life (as we know it, i.e. carbon-based), a planet that needs to be in a stable, not too eccentric orbit around a star of just the right size which is just the right distance away, etc etc, if you assume that the odds are even as long as a billion to one that the planet satisfies all the conditions, and you further assume that there are a billion billion planets in the universe, that would make for a billion planets satisfying the conditions. Given such odds, and even if you play with the odds quite a bit, it's far from unlikely that life exists elsewhere in the universe. After all, we're even now considering that life may have once existed on Mars, right next door.

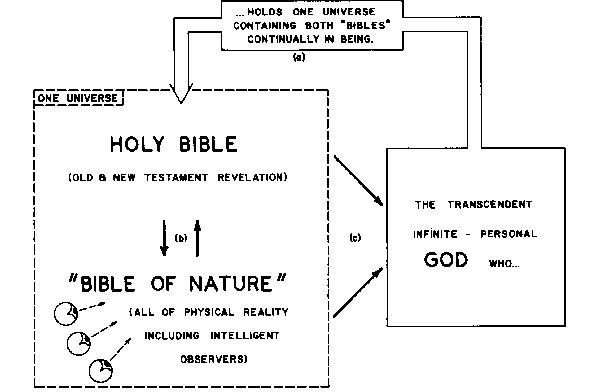

There's a great deal more to the anthropic principle than this of course, and some creationists have argued that a version of the anthropic principle, the strong anthropic principle, supports the idea of a designer of a universe which just happens to meet the conditions that support, somewhere within its vast extent, the existence of we humans. Again this argument suffers from the infinite regression problem, not to mention the massive redundancies involved, assuming, somewhat egotistically, that this universe was created essentially for the purpose of sustaining life on this little local planet (and that even the millions of species here are bit-players to humanity's central role).

The anthropic principle helps to explain, statistically, how life might've emerged on this planet, though it doesn't explain the chemical details. Those interested in exobiology are trying to create the original conditions that sparked life on this planet, and I believe there's a substantial prize on offer for the first person to create life as it might've been created out of the primordial soup a few million years ago. Not artificial life – the real thing. Once this improbable event occurred, though, life would've evolved along Darwinian lines in a series of not particularly low probability steps. However, pundits such as Mark Ridley have argued that developments such as eukaryotic cell life, and consciousness, are low probability events on a par with the origin of life itself, and that the three-stage development (life, eukaryotic life, conscious life) which has taken place on our planet might make it all the more unique. Dawkins and others argue that a higher frequency of low probability leaps reduces the likelihood of a creator/designer and that therefore creationists are just displaying their ignorance of what's involved when they jump on the origin of life conundrum as evidence of their deity of choice. In any case, if we do manage to reproduce the beginnings of life from the correct chemical soup, that'll be something else for the creationists to ruefully contemplate.

Dealing more briefly with the greater cosmological aspects of the anthropic principle, the central theme is of a finely-tuned universe – finely tuned, that is, to make our own life form possible, or even to make the creation of heavy elements possible. The physicist Martin Rees refers to six essential numbers, numbers which express six fundamental constants of the physical universe. If any of these numbers were smaller or larger than they are, life as we know it wouldn't be sustainable – they all lock our universe into a 'goldilocks zone' (and there's apparently some reason to believe these numbers are interconnected), creating just right conditions.

Some theists have scented an opportunity here. Surely this propitious (to us) state of the universe couldn't have come about by chance. A deity must've set the controls to the right levels for our sake. The first response is again to point to an infinite regress. Creationists try to argue that such an 'irreducibly complex' entity as this universe therefore displays evidence of design, and must have been designed by an entity more irreducibly complex than itself. But such an irreducible entity must itself have been designed by an entity even more irreducibly complex etc.

There are other responses. Obviously this universe is just right for us, or we wouldn't be here to contemplate it. That doesn't exclude the possibility of other universes, in which we aren't. Nor does positing a deity explain why things have worked out the way they have. It seems too obviously a self-serving argument, with a deity creating this 13 billion year old expanding collection of stars, planets, black holes, etc, just for the purpose of building us a bamboozling and tenuous home, so that he can watch us, guide us and make a more or less infinite range of decisions about our futures, all presumably while controlling and guiding every other nook and cranny of the cosmos. A view, moreover, with no evidence whatever to support it.

So much for my amateur ruminations on the anthropic principle. I wonder if I'll ever have cause to mention it again.

The dead birch in my back garden has fallen over in the wind, snapped at the base. Otherwise it's quiet.

I'm in a post-Christmas trough. No money for quite a few days, and money is energy. As to exercise, I probably need to link up with someone.

Tomorrow I'll write about Lord Palmerston's views on trade.

Labels: cosmology

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

Subscribe to Post Comments [Atom]

<< Home