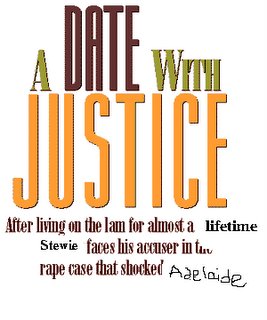

A few days before the arraignment, the police came to my house, the one I’m moving out of, to photograph it according to a request from the DPP. So, some eight months after my arrest, the so-called scene of the crime was to be visited for the first time. The officer who set up the visit, Constable Welsh, was the junior member of the pair who’s arrested and questioned me upon my arrival at Port Adelaide police station. On the phone he was much more relaxed, even affable.

He arrived at the house ahead of the police photographer, and apologized for the inconvenience. I showed him in, showed him the toilet door, and happily answered his enquiries by showing that, though the door was lockable from the inside, it could be opened from the outside with a mere twist of a fingernail. This information correlated with the little liar’s claim that the door was easy to open from the outside. So, it was all up with me. Next, we visited the front room, Andrew’s old bedroom. This was a key piece of evidence for, though during the interview at my arrest there was some story of my later having followed him into the bedroom and raped him a second time, in the subsequent written report of the police, the story was somewhat different. Apparently I’d followed him to the bedroom but he’d locked the door against me. As I pointed out to my lawyer, there were no locks on any bedroom doors. I was now able to show this to the good constable, to his great interest. I then asked, naturally, ‘why didn’t you have a look at this before you arrested me?’ The good constable fobbed this off apologetically. Apparently they didn’t think it was necessary, that it would get this far. And yet they’d arrested me. For rape.

Still, I didn’t feel too enraged. He seemed like a genuinely nice bloke, and I was relieved that an authority figure in the case was for the first time willing to treat me without either hostility or bureaucratic blankness. At our previous meeting, he’d handled himself with great nervousness, trying to rise to the seriousness of the occasion and to do everything with technical exactitude. Now, rather to my surprise, I found him keen to talk, struggling with the need for circumspection. We made awkward small talk about the house, and the near-identical one next door which he knew I was moving into. I explained how we’d managed to fit the two houses onto what had been one block, against prevailing advice, and then I gave a spiel about how housing co-ops worked. We discussed the travails of the Housing Trust, a subject of some interest to him, as his police work often entailed dealing with troublesome Trust tenants.

Yet after a few enthusiastic minutes, our conversation collapsed. We were silent for another five. The matter of the case loomed like an iceberg between us, tempting collision. I finally ploughed into it, regardless. ‘Anyway, my view on all this is to be very careful of the stories kids tell you – because foster carers have no protection whatsoever.’ I could see he was totally sympathetic – though his blaming of the DPP’s office for the fact that this matter hadn’t been cleared up struck me as a trifle disingenuous. ‘After the Nemer case, things have changed a bit with the DPP,’ he explained. ‘They wanna make sure, you know? And then I’ve heard they’ve got a backlog of cases about two years long.’

The constable’s remarks have prompted me to further thought on this matter of the DPP. A couple of years ago a new DPP was appointed by the state government. This was part of their law and order push. The DPP had come under a cloud because of a few highly controversial and much-publicised outcomes, most notably the Nemer and McGee cases.

In a broadcast for Stateline on May 6 2005, a few weeks after my last foster-charge was taken from my care, and a month or so before my arrest, the new DPP, Steve Pallaras, gave one of his first speeches. If the government was hoping Pallaras would fall into line with its ‘get tough’ policies, they would be gravely disappointed. Pallaras’ speech focused on government meddling with his office, on lack of funding, and on the lack of consultation around the Royal Commission called into the McGee affair, which he described as essentially a ‘politician’s picnic’.

These fighting words probably represented a calculated risk on Pallaras’ part. To stand up to the highly popular state government like this would mean putting the DPP’s own credibility on the line. Whether or not the previous decisions of the DPP had been mistakes, it was clear that there could be no more ball-ups, even if only on the level of public perception. If this meant hanging some lowly, powerless, even if innocent, foster-carer, out to dry for a while, then so be it.

I’m not pretending that I’m a vital figure in any of this, or even a dust-speck on the horizon, but the politico-legal climate does have its role to play. However, the question of whether the political battles being fought by the DPP have had any effect on my case is impossible to answer.

It might be more fruitful to look at the logjam of cases the DPP has to cover, and their lack of funds to do a comprehensive job. During a Stateline discussion on whether or not the DPP was in crisis, financial or otherwise – a discussion in which my own lawyer participated – the presenter, Ian Henschke, said this :

It’s a DPP in financial crisis. In fact, I'll go back to the Watkins case.* The DPP told the widow that 'We don't represent you, we represent the state'. So, in other words, what they're doing is they're making a financial decision about how they're going to run the case on behalf of the state.

To which my lawyer answered:

That's a very small part of the considerations about that. The choice about whether or not to run a prosecution for a serious offence such as manslaughter is ultimately going to depend on whether or not there are reasonable prospects of securing a conviction.

It would seem also that the prospects of securing convictions would depend to some degree on their funding. This might be a happy prospect for me, but I also happen to think it’s outrageous that my case or that of anyone else should be decided even partly on the basis of the state of the state prosecutor’s purse. But then, I suppose it has always been this way.

*Refers to a highly publicized case in which Andrew Watkins, a thirty-eight-year-old father of two, was struck down while riding his bicycle and dragged for several kilometres by Andrew Priestly. Priestly was gaoled for four years with a two-year minimum, but this sentence was increased after a public outcry and a DPP appeal.

The SA DPP’s prosecution policy is available online. The document emphasizes the point that justice must come well before winning. The duty of state prosecutors is first and foremost to lay the evidence before the court to the best of their ability, and they shouldn’t be reticent in so doing – indeed some of the document reads as if the adversarial system doesn’t exist.

From my perspective, the most important section of this document is entitled ‘The decision to prosecute’, which starts thus:

A prosecution should not proceed if there is no reasonable prospect of a conviction being secured. This basic criterion is the cornerstone of the uniform prosecution policy adopted in Australia.

.

This first statement is opened up and fully explored in subsequent paragraphs. However, I’ve dwelt on this long enough, for now. Let me finish the story of the police visit.

‘Well, meanwhile I’m waiting to clear my name and get on with my life,’ I said, and he nodded and shrugged and made sympathetic noises. So I went further. ‘You know the terrible thing about this is that, if we could’ve gotten together the people who worked with Andrew – professionally – this could all have been cleared up in a couple of hours. It’s just such a waste. I’m not too worried, I know it’ll be thrown out eventually, but in the meantime, my whole life’s on hold.’

‘Yeah, well I’m amazed it’s still going, we’ve talked to everyone. Amber – you know, Amber, his social worker? And we’ve been asked to look further into the Victor Harbour stuff, they’re very interested in that, but I mean that matter’s closed as far as we’re concerned.’

All this chat came to an abrupt end when the police photographer finally arrived. He didn’t know me of course, and treated me with the usual sort of police suspicion and disdain. He photographed the toilet, the front bedroom, and the lounge too. He had a few words to say about the front room, but I didn’t listen. Things would take their course. Afterwards, Constable Welsh – I’m sorry I never learned his first name – bade me an awkward farewell, not quite feeling free to wish me good luck…